Getting a Jump on Crop Drought with Aerial Photography and Infrared Technology

By Deanna Dames, Portland Farmers Market volunteer

You may know Portland Farmer’s Market vendor Martin Pitney of Gala Springs Farm for his sweet melons and delicious apples, but did you know that in addition to managing his own farm he also helps other farmers uncover early drought and other problems with their crops through his business, Photography Plus? We recently talked with Martin to find out how he got started with his photography business and what impact(s) early drought detection can have for our local farms.

It All Started in Hawaii

Early in his career, Martin was working for Amtac Inc. as an agronomist where he patrolled Hawaiian sugar cane fields to gauge their field conditions. As a “thirsty” crop (it takes about 240 gallons of water to produce one pound of sugar), it was essential to monitor cane field conditions so that the plantatio would not suffer expensive crop losses.

Sugarcane fields have dense canopies, so for efficiency sake, Martin took to the air to keep tabs on the large acreages of sugarcane, where he gained an entirely different perspective on the crops.

Later, when he was transferred to the Columbia Basin to oversee about four-thousand acres of potatoes, he also used aerial surveillance to monitor the crops and keep up with his rigorous inspection schedule. It was there where he decided to experiment with infrared (“IR”) photography to help him spot troubles in the field. In 1975, Martin started Photography Plus to provide this service to other farmers, helping them to identify crop issues in time to resolve the problem.

Photo courtesy Martin Pitney

How Infrared Technology Works in Photography

Infrared photography arose during World War II as a way to detect camouflage. If vegetation was not healthy, it would show up as a different color than the healthy vegetation. For this reason, it was also easy to spot where vegetation had been cut to hide a tent or camouflage nets. In crop management, IR photography works in the same way, producing nuances to images that are not possible with conventional photographic films.

In most cases, cameras rely on the sun’s energy to illuminate the surface to be photographed. Light is transmitted, absorbed, or reflected depending on the properties of the materials it strikes. Eventually, all light is either absorbed by some object or reflected. Light energy that is absorbed is converted to heat. Reflected light can be recorded by photographic film or electronic sensors.

Various crop factors, including drought, nutritional deficiency, or disease, can reduce or change the plant chlorophyll content so that its structural and physiological characteristics alters the way that crop reflects light. As chlorophyll absorbs most of the light from the red and blue portions of the visible part of the spectrum, the differences in reflectance can be captured by IR photography to distinguish healthy vegetation from stressed vegetation.

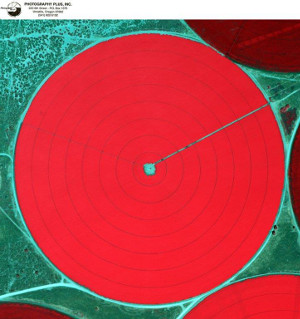

In the photos below you can see that healthy plants show up as bright red; and unhealthy plants show up as a more neutral color, dark spots, or circles.

Photo courtesy Martin Pitney

Compared to standalone aerial photography which only can only captured stressed crops 1-2 days before the problems can be visually seen, IR photography can help to identify adverse crop information 10-14 days before it can be visually detected. While it does not eliminate the need for farmers to go into the field, IR photography allows farmers to spend their time working on the problems, rather than looking for them.

Diagnostics is the Secret Sauce

While photographs can give farmers some information for early detection, it’s the really abstract patterns – many of which looks like a series of psychology tests – that help Martin to make a diagnosis for the farms. After years of working with the photos, Martin says he “can usually just look at the patterns in the pictures to diagnose 90 percent of the problem.” The initial patterns show farmers where they have potential problems with disease, flaws in their irrigation systems, irregular soil variations and fertilizer applications – all of which help determine a field’s nutritional and water requirements. But collecting and comparing aerial photographs over time also help farmers determine if the solutions they put in place the year before were successful, while also helping them prepare more efficient water management and conservation plans to optimize their future crop production, conserve water, and reduce unnecessary farm expenses.

Today, Martin runs Photography Plus out of Umatilla, Oregon, where his service does the same thing for his customers as it did for him when he was an agronomist – saves them time, money and legwork so that they can spend time fixing the problem instead of policing for it. He emphasizes that services like his are applicable for farms of all sizes – from small growers like him, to large farming corporations. In Martin’s experience, he says that, “having this advanced knowledge about the health plants your gives farmers (including his own farm) the ability to resolve the issue before there is irreversible crop damage.”

To learn more about aerial crop photography, contact Martin’s Photography Plus office or visit him at the Gala Springs booth next season at the PSU and King Farmers Markets, April through September.

Photography Plus

220 6th St

Umatilla, OR 97882

541-922-5132